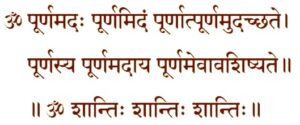

The introductory verse of Ishavasya Upanishad read as:

The meaning of the above verse is so profound that someone once said: “Let all the Upanishads disappear from the face of the earth – I don’t mind so long as this one verse remains.”

In this article we will dive deep into this verse and understand its meaning.

The above verse comprises following words:

Adah – that, Idam – this and Purnam – completeness

Purnam means completely filled – a filledness which is wholeness itself, absolute fullness and lacking nothing.

The verse is translated as:

Completeness is that, completeness is this

From that completeness, this completeness came

From that completeness, this completeness removed

What remains is completeness

Purnamadah Purnamidam

Purnamadah – completeness is that,

Purnamidam – completeness is this.

Adah (that): ‘that’ always refers to the unknown i.e. something remote from the speaker in time, place or understanding. It refers to a thing to be known – a thing which due to some kind of remoteness is not present for immediate knowledge but remains to be known upon destruction of the remoteness.

Idam (this): ‘this’ refers to something not remote but present – something immediately available for perception, something directly known or knowable.

Traditionally, however, ‘idam’ stands for anything (presently known or unknown) available for objectification i.e. for any external object, which can be known by me through my means of knowledge. Thus, ‘idam’ stands for everything available for objectification.

Also, all adah i.e. all things called ’that’ become ’this’ as soon as their thatness i.e. their remoteness in time, place or knowledge is destroyed.

Purnam (completeness): The nature of purnam is wholeness, completeness, limitlessness. There cannot be purnam plus something or purnam minus something. It is not possible to add or to take away from limitlessness. Considering the nature of ‘purnam’, ’that’ purnam must include ’this’ purnam and ’this’ purnam must include ’that’ purnam.

That (adah) in context of the verse

Purnam is total fullness which leaves nothing out. ‘This’ (idam) stands for everything available for objectification. ’This’ cannot be used to describe purNam because ’this’ leaves something out – the objectifier i.e the subject, I (aham). The subject I, (aham), is always left out when one says ’this’. If ‘I’ is not included then purnam is not completeness. Therefore, ‘completelness is this’ appears as a disputable statement. Thus, the real meaning of ‘that’ (adah), which is used in contrast to ‘this’ (idam) is I (aham).

Am I (adah) something to be known?

I (aham), the subject, is certainly not remote in terms of time or place. But perhaps ‘I’ may be remote in terms of knowledge. If in fact I do not know the true nature of myself as a soul in terms of knowledge. When that knowledge is gained, I will recognize that I (soul) am identical with limitless Brahman (divine consciousness) – all pervasive, formless and considered the cause of the world of formful objects.

Thus, the first two lines of the verse can be interpreted as:

Purnamadah – completeness is I, the subject (soul), whose truth is Brahman – formless, limitlessness, considered creation’s cause

Purnamidam – completeness is all objects i.e all things known or knowable, all formful effects, comprising creation.

Why use this (idam) and that (I) instead of ‘Everything is purnam’?

It seems unnecessary to say ‘I’ (that) is purnam and then to say ’this’ (which really stands for all the objects in the world) is pUrNam when one could just describe the fact and say: everything is purnam.

However, our everyday experience is that I (aham) is a distinct entity separate and different from ‘this’ (idam), this world of objects which I perceive. My experience is that I see myself as not the same at all as ‘this’ (idam). When I hold a rose in my hand and look at it, I (aham), am one thing and ‘this’ (idam), the rose I see, is quite another.

Shruti tells me that I (aham), and the rose, this (idam), both are limitless fullness (purnam). Therefore I must include the rose and the rose must include me. But that logic does not alter my experience of the rose as quite separate from me.

Furthermore, it is not my experience that either I or the rose are, in any measure, purnam, completeness – limitless fullness.

Completeness (purnam) cannot have a form

Completeness (purnam) cannot have a form because it has to include everything. Any kind of form means some kind of boundary. Any kind of boundary means that something is left out – something is on the other side of the boundary.

Scriptures reveal that what is limitless and formless is Brahman, the cause of creation and the content of ‘I’ (aham). Therefore, given the nature of Brahman, one can see that completeness (purnam) is another way to say Brahman. Brahman and completeness (purnam) have to be identical. There can only be one limitlessness and that is Brahman.

I (adah) cannot have form despite our formful experience

I (adah), the ultimate subject can have no form because to establish form there would have to be another subject, another I to see the form. The other I would then become the ultimate subject, which if it had a form would require another subject, which would require another subject endlessly. Thus, formlessness of I is confirmed as a logical necessity for the ultimate subject.

Whether ‘I’ (ahah), is formful or formless, my experience remains that I am not ‘complete’, and this world is different from me. Therefore, there is a relationship of mutual limitation, between the individual and the world. I seem to be a separate entity in a world of many different things and beings. My experience proclaims “differentness” – difference. But there can be no difference in completeness (purnam). Completeness requires that there be no second thing (non duality). Difference means more than one thing. The nature of experience is ‘duality’ – the seer and the seen, the knower and known, the subject and the object. When there is duality (difference), there is always limitation. I (aham) have this experience-based limitation.

When I turn to the Upanishads, it tells me that I am the limitless being who I long to be. But, at the same time, it recognizes my experience of difference. In this verse, the two separate pronouns I (adah) and this (idam), together comprise everything in creation. They are used to indicate completeness (purnam). This is done to recognize the experience of duality. It accounts for duality by negating experience as non real but not as nonexistent.

The verse objects to the conclusion of duality – not experience of duality. The conclusion that I am different from the world; the world is different from me. This verse contradicts it by stating that both ’I’ and ’this’ are complete (purnam).

To experience completeness (purnam), a literal elimination of duality is required. Completeness would be an intermittent condition brought about by a special kind of experience such as nirvikalpa samadhi in which all sense of limitation is gone. But that experience is also temporary. It is bound by time.

Above conclusion is not a matter of belief but a logical conclusion

The above conclusion is not a matter of belief but a ‘pramana’. A pramana is a means for gaining valid knowledge of whatever the particular pramana is empowered to enable one to know. For e.g. eyes are the pramana for knowing colour, ears are the special instrument for sound. The statements in the upanishads are a pramana for the discovery of the truth of the world, of God and of ourselves – for gaining valid knowledge about the nature of reality.

A qualified teacher would unfold the meaning of “completeness is that; completeness is this” by relating it to other statements of Upanishads and by using reasoning and experience. What is here called completeness (purnam), elsewhere Upanishad defines as Brahman. The Upanishad statement also describes Brahman as the material cause of creation, wherefrom all beings are born; whereby they live and upon death, they enter (Brahman). But no Upanishad statement directly names Brahman as the efficient cause.

Taittiriya Upanishad mentions – “He (Brahman) desired – Many let me be. Let me be born (as many)’. This requires that limitless Brahman, which is the material cause of creation, must also be an efficient cause. A limitless material cause does not allow any other to be the efficient cause – the existence of an ’other’ would contradict the limitlessness of Brahman.

Thus, in this verse, the statement that I (aham) and this (idam) each is complete (purnam) requires that though they appear different, they are identical. Elsewhere Upanishad identifies Brahman as the material and (by implication) the efficient cause of creation. This makes Brahman the complete cause of I (aham) and this (idam). Conversely, I (aham) and idam (this) are effects of Brahman. The statements of Upanishad here and elsewhere are logically consistent.

For ‘I’ (aham) to be ‘this’ (idam) and for ‘this’ (idam) to be ‘I’ (aham) they must have a common efficient and material cause. Consider an example, a single pot referred to both as ’that’ and ’this’. For ’that’ flower pot which I bought yesterday in the store to be the same as ’this’ flower pot now on my window, there has to be the same material substance and the same pot maker for both ’that’ and ’this’. It is clear that the ’twoness’ of ’that’ pot and ’this’ pot is functional only. ‘That and ‘this’ refer to the same thing which came into being in a single act of creation.

Similarly, both the seer (aham) and the seen (idam) are identical, being the effects of a common cause. The cause must be not only the material cause but also the efficient cause. The cause, being complete (purnam), nothing can be away from it. Therefore, if in addition to a material cause, creation requires an efficient cause, a God, then God, the creator is also included in completeness (purnam). Purnam (completeness) is the material-efficient-cause of everything – God, semigods, the world as well as the seer of the world.

Situation with two seemingly different things having common cause

Our ordinary dream experience provides a good example of a single cause which is both material and efficient. It is also an example of effects which appear to be different but whose difference resolves in their common cause.

In a dream both, the dream’s substance and its creator abide in the dreamer. The dreamer is both the material and efficient cause of the dream. Furthermore, in a dream there is a subject-object relationship in which the subject and object appear to be quite different and distinct from each other. The dream world is a world of duality. But this dream difference is not true (real).

When I dream that I am climbing a lofty snow-covered mountain, the dream I (aham) is nothing but I, the dreamer. The snow-capped peak, the rocky trail, the wind, the dream this (idam) i.e. the dream objects are also nothing but I, the dreamer. Both subject and object happen to be I, the dreamer, the material and creative cause of the dream.

Like a dream, in the first line of this verse the efficient cause and the material cause of I (adah) and of this (idam) are puram (Brahman). The experienced differences between I (the subject) and this (the objects) are unreal.

In the second part, we will dive deep into the other lines of the verse to understand their meaning.

Reference: Commentary on Purnamadah Purnamidam: Swami Dayanand Saraswati